Product Hub September 09, 2015

A Day in the Life of a Designer

Tag along with two super-busy apparel designers to learn how they conceptualize and churn out stunning embellished work – couture, movie sets, high-end retail stores and more

Tag along with two super-busy apparel designers to learn how they conceptualize and churn out stunning embellished work – couture, movie sets, high-end retail stores and more

Ever wonder what a fashion designer does all day? Or a Hollywood costume designer? It’s not all glamorous runway shows and hobnobbing with celebrities. Just as in any business, designers spend many of their working hours meeting, planning and figuring out logistics. To get a glimpse of the inner workings of the fashion world, Stitches teamed up with two very different designers on opposite coasts of the U.S.: In New York, we shadowed veteran designer Byron Lars as he planned out his whimsical, heavily embellished holiday collection; and in Los Angeles, we followed costume designer Camille Jumelle while she pieced together the wardrobe for an independent movie.

Day in the Life: Byron Lars

An expert at pattern-mixing and what he calls “embroidery problem-solving,”veteran fashion designer Byron Lars creates flattering garments with a woman&’ s figure in mind.

It’s a crisp, spring morning in the middle of April, but you wouldn’t know it in the textile agent’s office in the heart of Manhattan’s Garment District, where fashion designer Byron Lars perches on a utilitarian rolling chair, sifting through a rack of sumptuous Indian embroidery samples, mentally piecing together his upcoming holiday collection. Lars’ casual style – a fitted hoodie in dark stripes with subtle burnt orange piping, cuffed jeans, combat boots and a black paisley bandanna – is in stark contrast to the sparkling sea of sequins and stones at his fingertips, but his sure hands never falter, plucking an ivory ribbon, strung accordion-style with crystalline beads from the dazzling array.

“This is really great,”he says, turning to James Molina, owner of Tex Appeal Inc. “How much is this one, James? Do you have it in black with jet beads?”

As Molina checks on price and availability, Lars explains that the ribbons would be the perfect addition to a black dress he’s planning – a series of necklace-like embellishments embroidered together into a kicky cocktail creation.

Lars pulls another header from the rack: a glistening field of bugle beads, sewn together in a chevron pattern. He gently tugs at the silk organza backing. “It would be on a very tight shirt,”he muses. “This feels very rigid, no stretch. That’s the thing that scares me about it.”

“Beads are always fragile,”Molina agrees.

But Lars shakes off the hesitation, ordering a 24”sample of the beading, three rows wide – all in black – switching the base fabric to a cheaper polyester organza. The beaded fabric won’t be touching the skin on the finished garment if it goes into production, so there’s no benefit to the added cost of a luxury fabric. “If it’s going to be real, it’s going to be on poly organza,”he adds. “That’s just a waste of silk.”

Over the course of half an hour, Lars orders several other embellishments, including a length of rubberized chain trim atop leather. “Just the idea of rubberized chain makes me want to rubberize everything,”Lars says with a grin. Next to him, stylish and efficient in a black-and-white dress, fishnets and green-rimmed glasses, his longtime assistant, Sheila Gray, writes up purchase orders and snaps quick smartphone pics of headers he’s interested in, but not yet ready to buy.

“I think that will do it for us today,”Lars says, and the pair head across the hall of the office building on West 37th Street – right into the Byron Lars Beauty Mark showroom – to drop off some goods and take a quick break before their next vendor appointment. As he waits, Lars looks over garments from his spring 2015 collection and ponders the role embroidery techniques play in his work. “We do quite a bit of embroidery, but I don’t usually approach it like that,”he says. “A lot of it is more like embroidery problem-solving.”He points to a black taffeta trench that morphs mid-way into a gray sweater coat. Lars used embroidery to soften the fabric transition, so there wouldn’t be a visible seam on the piece.

He grabs another spring garment from the rack: a chic, fitted jacket that includes “everything and the kitchen sink.”Lars pulled inspiration from some multicolored textural Guatemalan fabric he found in China, which he paired with a slightly more muted Italian textile for the sleeve. “The two just spoke together,”he says. He added various trimmings and embellishments along the way, including hand-stitched sequins and a column of tiny worry dolls parallel to the buttons. The inner lining features a machine-embroidered Mexican sugar skull: “It’s the kind of thing when you own something and you open it, even though you’re the only one who knows it’s there, it just makes it that much more special to you.”Lars also used machine embroidery to create some elastic smocking to make the jacket’s narrow fit less restrictive.

Considered piece by piece, the jacket shouldn’t work, but it’s more than the sum of its parts: transcending the potential for gaudiness to become classy and elegant. “That was something I learned a long time ago,”Lars says. “To quiet garments down, you have to make them super-busy, so your eye doesn’t know where to go and it almost becomes solid activity. People say, ‘You need a focal point.’ And I’m like, ‘No, I need so many focal points that it becomes a solid carpet.’”

Blast From the Past

Each season, fashion designer Byron Lars covers a large corkboard with a slew of fabric swatches, creating an easy reference and inspiration point as he pieces together his collection.

Byron Lars’ Timeline

- 10 a.m. Meeting at Tex Appeal Inc.

- 10:49 a.m. Meeting at Textile Portfolio Co.

- 11:30 a.m. A quick walk to the studio

- 12:28 p.m. Lunch while checking email

- 2:06 p.m. Choosing fabrics for his holiday collection

- 4 p.m.Appointment with a fit model

- 6 p.m. Finishing work for the day

At 10:49 a.m., it’s off to the next vendor meeting, just down the hall from the showroom. Like Tex Appeal next door, the Textile Portfolio Co. is small, but full of finery. The walls are lined with clothing racks, three deep, hung with rich fabric samples – lace, sequins, embroidery, eyelet, jacquard and more. Textile agent Elayne Aschkenes greets Lars and Gray at the door, wearing a pair of metallic-toned oxfords that Gray immediately covets. “Everybody likes these,”Aschkenes says. “I got them in Paris. They weren’t even expensive.”

Lars and Gray apologize for having set up their appointment with Aschkenes at the last minute, but she waves them off: “I love you guys. You’re like my easy customers. You help yourselves.”

Lars heads to one of the clothing racks and begins pulling samples onto the broad, black table in the center of the room: sequined “O”shapes in white, black, silver and gold; a gold and black sequined leopard pattern; a double flower appliqué in black; a wisp of black lace made of a “spongy tech fabric.”

At 11:09 a.m., a bald man walking down the hall outside the Textile Portfolio Co. does a double-take, then knocks on the glass-front doors. Aschkenes lets him in, and the man heads straight for Lars: “You’re Byron Lars, aren’t you? You’re terrific,”he gushes. “Years ago, you had that blouse. You were hot for blouses.”

Turns out, the man used to be a neighbor of Lars’ previous assistant. They spend a few minutes reminiscing, as Gray writes up purchase orders, consulting with Aschkenes to ensure their custom requests won’t be misinterpreted by the factories in China that produce the textiles.

By 11:30 a.m., Lars is ready to make the trek to his studio on the east side of 37th Street. The studio, he says, “is always a mess,”but also the place “where we make real decisions and talk about the next place to take things.”The encounter with the man from his past has put Lars in a contemplative mood. As he drags a zebra-print roller bag down the bustling street, past tourists lounging at outdoor tables set up on Broadway – “Now that Broadway’s a park, you scarcely ever have to wait for a light.” – across Fifth Avenue, past food carts and men in gray overalls squeegeeing picture windows, he tells his origin story. Lars got into fashion in high school, when he coveted a pair of designer pants that were out of his financial reach. He asked a friend who sewed to make them, but she declined, offering instead to teach him how to sew, so he could make the pants himself. The pants were a hit, and he starting designing and sewing his classmates’ prom dresses.

“To quiet garments down, you have to make them super-busy, so your eye doesn’t know where to go and it almost becomes solid activity.”

Byron Lars, fashion designer

When he graduated, Lars moved from northern California to New York to study at the Fashion Institute of Technology, launching his first collection in 1991. “I made the samples myself out of my apartment,”he recalls, as he dodges passersby, squeezed into a narrow, scaffolding-covered sidewalk. “I carried them on my back and took them to stores.”Henri Bendel, an upscale women’s specialty store on Fifth Avenue, was the first to order his clothing, giving Lars the chance for a window display. He borrowed money from his grandfather to fulfill that first shipment. Orders from stores like Bergdorf Goodman and Saks Fifth Avenue followed, launching Lars into the spotlight.

Lars and his longtime assistant Sheila Gray pick through embroidery and beading samples at Tex Appeal Inc., seeking the perfect embellishments for Lars’ holiday collection.

Back in the Studio

At 11:52 a.m., Lars steps into an unassuming beige building, a few doors down from the Polish Consulate, and heads down a dark, rickety staircase. “The only thing missing from this entrance is a guy on the other side with chloroform,”Lars jokes, before unlocking the door to his small studio. Paperwork and fabric are piled high on several long tables in the center of the narrow room. The walls are lined with metal shelves; a few sewing machines sit at the far end. Near the door, a large corkboard is draped in the tones and textures of Lars’ Fall 2015 collection: here a scrap of deep blue lace butts against a bold black-and-white houndstooth print, there a gold appliqué daisy is pinned over a subdued blue and gray plaid.

Lars sweeps a bag of walnuts and a few stray ketchup packets from a table, replacing them with a handful of gold findings: swooping birds, fluttering insects and various mechanical gears. The insects and birds will be connected to the gears, perhaps with elastic thread to create movement; and the gears will be arranged over a sheer heart shape on a basic black sheath dress. “The ultimate idea of this is that the heart is the motor and these natural elements get animated by that,”Lars says.

Career Highlights

- Studied at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York

- First collection came out in 1991

- Designed a limited-edition line of couture Barbies for Mattel

- Clothing has been sold in Saks Fifth Avenue, Bloomingdale’s, Bergdorf Goodman, Neiman Marcus and over 100 specialty stores

- First Lady Michelle Obama has worn several of his dresses

- 2014 recipient of the Pratt Institute Fashion Visionary Award

Lars doesn’t do much sketching or sewing while he’s in New York. “I have a vague idea of everything in a collection, then work it all out in China,”he says. Lars spends three months of the year in Shenzhen, developing catalog samples and overseeing production. Creating samples at the factory where the clothing will be produced helps to keep costs down and ground Lars’ “pie in the sky”concepts. “We get the factory involved in problem-solving,”he says. Because the holiday collection is on a tighter development schedule than the fall and spring seasons, Lars does more of the planning in New York. The mechanized heart dress, for example, will be mocked at his New York studio and sent with a pattern to the factory in China. “The schedule is too aggressive,”Lars says.

“At the end of the day what my customer has come to appreciate are the touches that really make them look better.”

Byron Lars, fashion designer

At 12:28 p.m., Lars and Gray sit down to lunch in the studio, sipping green smoothies and munching salads. Lars flips open his laptop to check his emails and “put out fires.”Gray sits opposite him, typing away on her own laptop. Lars starts to ask her a question, but she shushes him: “Hold on, baby, I’m doing social media,”she says, as she updates the official Byron Lars Beauty Mark Facebook page. “I have a habit of typing what you say.”The duo have an easy rapport from a decade of working together. Gray handles Lars’ public relations, order follow-up and logistics – helping Lars bring order to the chaos of his schedule.

The Messy Art of Fabric Mixing

At 2:06 p.m., Lars abandons his email and heads over to a heap of swatches he’s considering for the holiday collection. The mess, he says, is part of his fabric-mixing process. He sees which patterns and textures play off each other, and “there’s no way for it to be orderly.”Lars picks up a strip of ivory and gold floral lace, wincing: “This is hideous. I hope I didn’t buy it.”Then, he tilts his head. “It would be nice if I dyed it for spring.”

He opens a yellow DHL envelope and unpacks some headers: knit fabrics in shades of pink, orange, black and white with of metallic thread. The samples are from a Turkish mill Lars discovered. “Their prices are really great, and the quality is really great,”he says. “That’s a nice combination.”

At 4 p.m., Carolina Rommel, a leggy, brunette fit model arrives at the studio. Lars pulls out a sparkly gray sweater dress with subtle striping that just arrived back from the factory. Yanking at the zipper, he frowns: “I can’t even unzip this, so that’s a problem.”Once the zipper unsticks and Rommel is dressed, Lars examines her from all angles, tugging at the hem. He points to few flaws in the fabric, where the stripes are uneven. “That’s something to watch for,”Lars says. If the fabric has enough similar flaws scattered throughout the run, it could affect garment cost and production. As Lars notes areas where the fit needs to be tweaked, Gray shoots video of the session, recording Lars’ notes so he can relay instructions to China.

Another issue Lars sees is that the zipper is ever-so-slightly too long, which could cause discomfort and fit issues for wearers. For Lars, the underlying structure and fit of his garments is just as important as the embellishments on the surface. “At the end of the day what my customer has come to appreciate are the touches that really make them look better,”he says. His dresses are a clever interplay of sexiness and modesty. That means enhancing and supporting the bust and rounding out the hips, but also including a nude lining to mask the sheer parts of a garment. Even the lining is thoughtfully executed: scalloped at the bottom to soften and conceal its existence, with a layer of taupe or black netting over a rose-toned base. “It’s much more flattering than flesh-toned lining. That doesn’t look like real skin. It looks like a Barbie doll under there,”he says, adding: “Not that there’s anything wrong with Barbie.”After all, Lars once designed a line of limited-edition couture outfits for Mattel’s iconic fashion doll.

By 6 p.m., Lars is done for the day, a few steps closer to finishing his holiday collection – he wants it to be ready by the end of September. There’s a lot of work to be done before the dresses make the leap from his mind to a store hanger, but Lars isn’t too worried. “We’re just going to go full throttle and hope they finish the bridge before we get to the chasm,”he says with a laugh.

Theresa Hegel is a senior staff writer for Stitches. Contact: thegel@asicentral.com; follow her on Twitter at @TheresaHegel.

Day in the Life: Camille Jumelle

When she’s not designing custom beaded gowns for red-carpet clients, Camille Jumelle brings her keen eye for detail to movie sets – putting together realistic, thoughtful costumes for independent films.

The residential parts of North Hollywood are solid and no-nonsense, the streets filled with postwar middle-class homes with kids playing in their yards and the hum of backyard pool filters filling the air. But on a busy street two blocks from the Ventura Freeway, in costumer Camille Jumelle’s condo, it’s Paris. The building’s deceptively unexceptional entryway leads to an atrium courtyard with a fountain, and Jumelle’s pied-à-terre is an oasis of quiet elegance with high ceilings and dusty-rose walls, recessed indirect lighting, period furniture and specialized art. One half expects Coco Chanel to come around a corner smoking a Gauloises and offering you a flute of Veuve Clicquot.

For Camille Jumelle, there’s a lot more to being a costume designer than picking a pretty outfit for an actor. When she works on a film, she reads the script at least four times to get a better sense of the characters and determine sartorial needs.

Jumelle, followed by her dogs Coco and Tiffany, glides through the condo, which is in mid-remodel. The white-on-white bedroom and extensive in-transition wardrobe area with shoe storage and vanity with light-haloed mirror contrasts with the stainless-steel-and-black-granite kitchen where she pours coffee.

“How I live represents how I treat my work,”she explains. “To a level of beauty, of class, of sophistication. Well-appointedness. That’s what people expect from my work. When a director of a low-budget project says ‘Just go get it at Target,’ it’s a dagger in my heart. Yes, I get that you just want me to get it at Target, but not everything there is going to work. Once you show people the difference, they like it, and they’ll always opt for the better.”

It’s also how she operates when she designs pieces for her own fashion line, Couture Junkie, or when she creates custom gowns on commission. “I’m used to doing red carpet gowns for the Oscars,”she says. “What women are looking for in their gowns is something that no one else is going to have. My gowns can start at $3,000 for a sheath dress and go all the way up to $100,000, depending on the beading. Some of the beaders I work with come from [the house of] Lesage in France. These women are artisans, and they can take a fabric panel and put it on a rack, and it’s like needlepoint with beading. It’s an art form.”

Ride ’Em, Cowboy

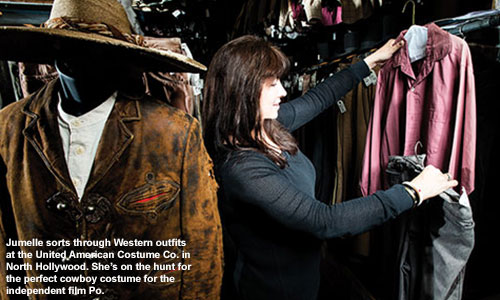

Today, however, Jumelle is assembling a cowboy costume. Her first stop of the day is to the United American Costume Co. Also in North Hollywood, in a light-industrial building near some railroad tracks, it specializes in Western and turn-of-the-century costumes. “The man who founded it did all the big Westerns with John Wayne and John Ford. He and his daughter pride themselves on the history of costumes and the history of filmmaking,”Jumelle says.

The history of filmmaking is on display starting at the front door at United American Costume, with props in glass display cases and full-size movie posters framed on the walls, many of them autographed. The small entry leads to large warehouse-like rooms, where costumes hang in racks that stretch up to the ceiling 20 feet above.

“You know where the cowboy stuff is,”a United American employee says, walking Jumelle past a worktable filled with sewing equipment. “You have your cowboy vests, you have your rough shirts and your pants, and your boots. Everything you need is here at your fingertips. Let me get you a rack to carry stuff and a ladder.”

“I love it here because everything is organized,”Jumelle says. “Everything is clean, and very detailed.”Signs on a nearby rack say “Loincloths, Wool,”“Loincloths, Leather/Suede,”and “Indian Tunics.”One large rack marked “Doubles and Triples”holds identical shirts and pants in sets of two and three for backup in case of on-set mishaps.

“The reason things cost more is because of the oil, dirt, the time it takes to distress something. That’s what brings the character to the garment and to the actor. I’m looking for a realistic costume. I usually have a notebook with the actor’s sizes,”Jumelle says, consulting it. “He’s 6’4”, 176 pounds, his waist is 34”but he likes it to be between a 33”and a 34”.Size 11-1/2 shoe. He told me if I go to an 11 it’s too tight. I always ask an actor what their hair color is and their complexion is. It helps me figure out what will look good on them.”

The cowboy costume is for actor Andrew Bowen, who plays multiple roles in Po, an independent movie in production. “What I try to do is look at a shirt, and picture a dark-haired good-looking gentleman, and what’s going to make him pop on screen. I want him to be vivid,”she says, flipping through a rack of well-worn cowboy shirts. “If I used a muted color like this beige thing, I don’t think it would pop as much. I can make this pop with a vest. I also try not to get itchy fabrics for my actors if at all possible – they’re in it for eight or 10 hours at a time. I think of that. Sometimes it can’t be helped to be true to the period, so I’ll either back it or line it.

Camille Jumelle’s Timeline

- 10 a.m. Head to United American Costume Co. to put together A cowboy costume for the movie Po.

- 1 p.m. Move on to the Po shoot at Avenue Six Studios in Van Nuys, a no-frills working studio for independent films, commercials and audience-participation infomercials.

- 3 p.m. Arrive at Studio Services office of Bloomingdale’s in Sherman Oaks Fashion Square. This branch of the department store offers entertainment-industry costumers professional services including show-specific billing and delivery.

- 4:30 p.m. Jumelle heads home after selecting the final costumes for the day.

“A good costume designer will bring things to an actor and a director that they haven’t even thought of. I did a detective movie, and the first thing I asked my actors was, ‘Where are you going to pack your gun?’ That’s going to alter how I’m going to dress them. A good actor appreciates that. I’ll read a script four or five times, so I get acclimated to the characters, and I’m tabulating what it’s going to cost me. I may just use the best and fudge what’s underneath it, which kills me, but sometimes you can’t achieve that. I like when an actor knows that I went to the ends of the earth for them, to make them happy. If you feel right in your clothes, you’re going to perform better.”

Quiet on the Set

After two hours assembling the perfect cowboy outfit – shirt, vest, pants, belt, hat, duster coat – Jumelle takes it to the Po set in nearby Van Nuys, arriving just as the crew is breaking for lunch. The production caterers have laid out a feast, with large beef ribs grilling on a barbecue and a buffet of salads, hamburgers, vegetarian lasagna, side dishes, desserts, bottled waters and soft drinks.

Career Highlights

- Studied at Parsons School of Design and the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York

- Member of the Costume Designers Guild

- Member of the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences

- Film credits include The Prince and Psycho Beach Party

- Celebrities have worn her gowns on the red carpet of many awards shows, including the Golden Globes and the Academy Awards.

Jumelle greets writer-director John Asher, then heads off to her colleagues in the costume trailer to hand over the cowboy outfit. Asher’s film is about a single father raising an autistic son on his own. The boy spends much of the movie in an imaginary place, called the “Land of Color,”where he interacts with several characters – a pirate, a cowboy, a knight, an astronaut – all played by the same actor. “A lot of people aren’t sure if autistic kids have typical behavior, but in their heads, [autistic kids] don’t know if they’re typical or not. They’re just enjoying life,”Asher says. The characters Po meets, he adds, need to look authentic and not in a “cheesy way or a cheap way.”

The bulk of the costume budget is going into those costumes worn in the Land of Color. “It’s all about subtleties, in everything from production design to costume design,”Asher says. “Camille and I had a discussion ahead of time, and we decided on earth tones for the real-life stuff. That way, when you go to the Land of Color, things will pop. By design. If you were to look at everybody’s wardrobe right now, it’s mostly earth tones.”

Studio Services

As the cast and crew get ready to shoot the first scene after lunch, Jumelle jets off to buy a new wardrobe at Bloomingdale’s in Sherman Oaks, near Van Nuys, for later scenes in the movie. This suburban Bloomingdale’s has a separate, unmarked street entrance for Studio Services. Jumelle rings a doorbell and is buzzed in, and welcomed by the staff. The walls are covered in ribbed dark gray cloth, with a pod coffee machine near a closet for jackets and tote bags, so studio buyers can travel light. Above a couch is a collection of framed original designer sketches, in bright splashes of color, with fabric swatches attached. A large Bob Mackie signature adorns a sketch of a gown worn by Cher.

Affixing a small, but noticeable “Studio Services”sticker to her black top – “This way I won’t get approached by salespeople”– Jumelle spends the next 90 minutes walking the clothing sections, seeking outfits for unshot scenes in Po. She’s careful to match the colors to the earth tone palette and the characters, rejecting a flowered cotton nightgown as “too cute for a mother, this is for a teenager” and riffling through the bargain racks for hidden treasures that can catch the eye and keep the costume budget down.

“When a director of a low-budget project says, ‘Just go get it at Target,’ it’s a dagger in my heart.”

Camille Jumelle, costume designer

After selecting several pieces, Jumelle takes them back to the office, through a doorway marked with a discreet “Studio Services”sign near the ceiling, and hands them to a clerk.

“Is this for Po?”the clerk asks, sizing up the clothes.

“Yes, Po, you’re right,”Jumelle replies, flipping through envelopes in a small wire rack. The envelopes bear the names of soap operas, episodic dramas, sitcoms and studios. “Is there anything for me in here?”

“I don’t think so,”the clerk says, removing the antitheft tags from the clothes. She gestures to a register: “You need these right now?”

“No, in a couple of days.”

“There’ll be a bill in there for you next time then,”the clerk smiles.

Leaving the store through the unmarked door and back on the street, Jumelle reflects on the duality of being a costumer and a costume designer.

“My background is to create and make things. I know where to get things dyed, where to get things cut. I know how to get things done for the industry. Little things add up to a lot. It’s great to be able to go into a store and do a Po. It’s a whole other thing when you’re creating it,”Jumelle says. “Clothes can look new if it’s for a magazine, but if you’re doing a movie, everyone is supposed to think these clothes are of that person you’re seeing on the screen. If they’re not distressed properly, if they don’t look worn, you just did a major disservice to yourself as a costume designer, but also to your director. If you’re looking at a war movie and the guys are supposed to be in the trenches but they look clean, would you believe they were really in the trenches? A lot of girls call themselves ‘stylists,’ and that’s what they are. They’re not costume designers. They think that all it is is picking up a pretty shirt and putting it on somebody.

“But it’s so much more than that. My job is to make people comfortable in who they’re portraying,”she says.Carlo Panno is a contributing writer for Stitches.

Product Hub

Find the latest in quality products, must-know trends and fresh ideas for upcoming end-buyer campaigns.