Product Hub March 03, 2015

School of Stitching

Art and fashion students at institutions like the Rhode Island School of Design and Kent State University are experimenting with the latest industry technology, taking embroidery into uncharted territory. By Theresa Hegel

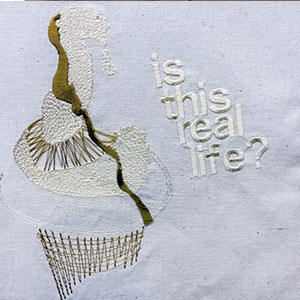

Mostyn Griffith, a lanky freshman with a mad scientist coif and thick-framed, black glasses, pins a creased rectangle of muslin to the classroom wall. Next to him, Tess Wagman, a pre-Raphaelite blonde in an Eeyore shirt, puts up her own muslin scraps. She glances at Griffith's work – a gold and cream abstraction with the words "Is this real life?" running alongside in satin stitches – and points: "This kind of looks like a funky mushroom."

In the meantime, Griffith is struggling to perch a canvas thick with gesso-soaked embroidery from a flimsy set of thumbtacks. Eventually, Griffith gives up, handing the thread painting to the waiting arms of his instructor – a dapper man in a blue-check button-down shirt open at the collar, with a neatly trimmed beard and a thick mustache waxed up at the ends.

The latest "crit" in textile artist Michael Savoia's digital embroidery class at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in Providence is well under way. The students – a baker's dozen of undergraduates and graduates in a diverse range of disciplines from jewelry to architecture – are gathered in a loose semi-circle around the front of the classroom, ready to discuss their latest explorations with the medium.

Savoia has been teaching the class for the last three years, ever since he uprooted his high-end embroidery company, Villa Savoia, from West Hollywood to a studio in the heart of Providence. His work has been featured in publications like Architectural Digest, and his client list includes Thomas Pheasant and The Wiseman Group; despite a long and lauded career in the embroidered arts, however, Savoia still finds himself regularly wowed by the intuitive leaps his students make, as they transfer their digital savvy to needle and thread. "After just two days in class, I was bowled over by what they've done," Savoia says. "This group is particularly adept with [digitizing] software."

For Savoia, it's crucial to educate the next generation of influencers in the apparel and design world. Otherwise, he says, the embroidery industry will never evolve or grow. He wants his textile students, in particular, to have an awareness of the medium when they enter the workforce and start landing jobs at top apparel companies like Levi or Nike. "When more people understand embroidery, it'll raise a call for a finer product in the marketplace," he says. "They'll insist on it."

Other industry professionals echo his sentiments. Jay Fishman, owner of the Wicked Stitch of the East, a digitizing firm in Cleveland, believes it's important to get art students excited about the possibilities of the decorated apparel industry, showing them how it can be a lucrative career choice for a creative professional. "Embellishment opens up a world of possibilities for students as they learn about working in different substrates," he says. Fishman has given lectures to college students, educating them about the history of embroidery. "It's important to me to keep this industry going for years to come," he adds. "I teach our history and speak in terms of the future."

Securing the Future

Securing the industry's future is one of the reasons Stitches helped RISD establish its embroidery program several years ago, procuring a Tajima machine at a reduced price from Hirsch International. Initially, the school hired Joyce Jagger, The Embroidery Coach, to provide three days of onsite training on the equipment. Eager to share his expertise, Savoia was later hired to teach a five-week digital embroidery course each winter and lead independent studies the rest of the academic year.

Savoia's month-long class begins with an accelerated overview of digitizing software and the care and feeding of the embroidery machine. Savoia gives students a primer in various stitch types – from steils to complex fills – and then turns them loose to experiment with their newfound knowledge. "I like the creative aspect that the students bring and how they can instruct each other through their pieces," Savoia says. He tries to steer his students away from the expected, asking them to abandon "all preconceived notions of what embroidery is" and start from scratch. He's particularly disdainful of replicating what's readily available in the commercial world. To students interested in creating military-style emblems and patches, he sniffs: "Do you really need to recreate something that you can buy for $25?"

During the classroom critique, however, Savoia is generous with praise, gently nudging his students to see their mistakes and dispensing advice on how to tweak their designs to best represent their artistic vision. Consider freshman Tristan Hsu. He pins two unfinished pieces to the classroom wall for review: One depicts a crowd of people, all clad in orange robes. From afar, the embroidery resembles flames more than figures. "This one is really lush texturally and beautifully colored," Savoia says. The second is a sort of triptych, showing a woman sitting next to a potted plant in the leftmost panel. The other panels are a sea of blue, with pink cross-hatches emanating from the top corner, like a branch dripping with cherry blossoms. "I'm trying to use the machine and software to go for a more illustrative feel," Hsu says. "I imagined how I would run the direction of lines and shading if I were drawing it by hand."

Classmates like how the second piece resembles "one of those three-panel church paintings that tells a story" and admire Hsu's control of line and ability to create small shapes. To Savoia, the embroidered artwork "almost has a quality of hand," looking more like hand-stitching than something run through an industrial machine. "It's an elegant little thing," he says.

Still, there are issues: Hsu created the seated figure with a complex fill used as a bi-satin, rather than treating each shape individually in the software for more control, Savoia says. Hsu also learned the importance of pathing: A thin, dark line cutting across the blue sky in his design is attached to the embroidery, and not just a stray thread caught under the machine. Clicking the proper box under density settings would have routed the thread along the outside edge of the stitching, rather than down the middle of the field. "I just completely forgot to change the settings," Hsu says, adding that it took him about four hours to sew out his two pieces, thanks to plenty of thread breaks. "I started over a lot."

Addressing Problem Areas

Savoia expects the students to forget much of what he's taught them in those introductory embroidery lessons, which is why the class is less lecture-focused and more self-directed and hands-on. When a student runs into a problem, however, Savoia is there to help, as he is after the critique when graduate student Emily Grego is trying to figure out the trouble she's been having with her sew-outs. Grego, a jewelry major, has been translating her jewelry designs into embroidery, and ran several unsuccessful tests of an elongated pendant in yellow and gold shades. Much of her jewelry is created using 3-D printing technology, and Grego says she found it a fairly easy transition between the software used in each discipline. The hardware, on the other hand, has given her pause: "I had a lot of problems with the tension and the density of the machine."

While the other students retreat to their computers to flesh out their final projects, Grego and Savoia head to the small adjoining room that houses the embroidery machine. The sleeves of her oversized, off-white sweater pushed up, Grego hoops a swath of muslin and loads it under the 15-needle machine. When everything is ready, she steps aside and turns on a bright swing-arm lamp, giving Savoia space to hunch over the embroidery machine. He fiddles with the black knobs at the top: "First problem," he says a few seconds later. "The thread's not under the tension knob." He makes a few other adjustments, and Grego's piece sews out with ease.

It's a common issue, Savoia says after giving the rest of the class a quick refresher on rethreading the embroidery machine. "I have to retension the machine every week. It's kind of exhausting," he adds. "Tension is one of the hardest things to understand and conquer. I struggle with it myself."

Despite those small frustrations, Savoia is in his element in the classroom, guiding these beginner embroiderers to greatness. And, he notes, he learns as much from his students as he hopes they're learning from him. "Some of the stitch combinations that they instinctively put together have been instructive for me," Savoia says. "Everyone is informing each other."

THERESA HEGEL is a senior staff writer for Stitches. Contact her at thegel@asicentral.com and follow her on Twitter at @TheresaHegel.

Embroidery High

Machine embroidery is also on the curriculum at a handful of high schools across the country, with educators encouraging students to start their own small decorated apparel businesses.

At Great Falls High School in Montana, family and consumer science teacher Kathy Goodman launched Bison Wear two years ago for her fashion design class. The students sell spirit wear to their peers and take logoed apparel orders from local companies. "I knew it would be a great opportunity for the students," Goodman says. "They get to be so involved in the entire process of the embroidery business, and having the hands-on experience makes it more like a job than a classroom."

Goodman received several grants to purchase a single-head Melco Amaya embroidery machine for her students; since then, however,

Bison Wear has been able to run off its profits, with Goodman able to add equipment for cutting large appliqués and creating rhinestone designs to the classroom. Since starting the Bison Wear business, Goodman's fashion design class has grown in popularity. "They love it," she says. "When they see their clothing being worn throughout the halls of the school or a jacket at the grocery store, they can say, 'Wow, I'm the one who did that.' They take a lot of pride in that." For Gregory James, a junior at Great Falls High School, the class has been a dream come true. "Fashion design is something I've always lived for, and have had a desire for ever since a young age," he says. "It requires hard work and dedication, [but] I've come up with so many unique embroidery ideas."

Over in Shelby, OH, Bill Dichtl purchased two Pantograms single-head embroidery machines for his graphic arts class at Pioneer Career & Tech Center. As juniors, every student at the school receives four T-shirts embroidered with their program's logo. Dichtl decided to take some of the financial burden off the school, while giving his students practical job skills at the same time. "It was a no-brainer to bring the embroidery machines in," he says.

Dichtl's students are learning the basics of digitizing and machine maintenance. "There have been times where they've had to switch the sewing order, to make the blue sew on top of the black or vice versa to make a logo look better," he says. "They just love watching it sew out."

In addition to sewing school T-shirts, the graphic arts students will work on personal projects, oftentimes creating presents for friends and family. One girl created artwork that looked like the barn on her family farm and sewed the design on a T-shirt for her father's Christmas present last year. He cried when he received it, Dichtl says.

One thing Dichtl won't do, however, is take work away from local embroidery shops. His students only accept outside work from nonprofits. "I can't compete with companies with paying employees," he says. "That's not fair if I steal the work from them and then ask them to hire my students. That doesn't work out too well."

Fashion Makerspace

Linda Ohrn-McDaniel, a tenured professor at Kent State University's fashion school, created this dress in the TechStyleLAB as part of her academic research.

Via Stacey, a senior in fashion design at Kent State University, remembers holding her breath the first time she used one of the embroidery machines at the Ohio school's TechStyleLAB. "I was afraid it would mess up," she admits. But the Celtic knot she drew and digitized last year ended up looking exactly as she'd hoped. "It came out awesome. Watching the machine sew out something I created is probably one of my favorite feelings in the world."

Now, Stacey is using the school's lab to investigate whitework embroidery, exploring techniques from the Elizabethan era onward. The modern twist? She's using jellyfish as her subject matter, rather than recreating a more traditional design.

Stacey is just one of many students taking advantage of Kent's lab. Besides embroidery machines, the TechStyleLAB houses equipment for digital textile printing, 3-D printing, laser cutting and a body scanner. "It's sort of like a makerspace for digital investigation when it comes to clothes," says Kevin Wolfgang, manager of the lab. "The idea is that whether you're in the fashion school or on or off campus, the lab gives you open access to digital technology."

Wolfgang says Kent's fashion school came up with the idea after a faculty member visited a digital printing makerspace in Edinburgh, Scotland. Wolfgang encourages students to step outside their comfort zone and find nontraditional uses for embroidery and the other equipment in the lab. Students and other lab-goers have thrown feathers under the needle and experimented with embroidery stitches to create darts, seaming and pleats on garments, Wolfgang says.

About one-fifth of the lab's patrons come from off-campus, whether quilting clubs or textile manufacturers. There are even a few New York-based designers who work in the TechStyleLAB, Wolfgang says. The lab is free, except for material costs. Wolfgang's only requirement is a spirit of collaboration; there's no such thing as a nondisclosure agreement in the lab. "It's important to work with the community, and it's great for the students to see what professionals are doing," he says. "Nobody's going to steal someone's ideas. They're too busy working on their own."

Product Hub

Find the latest in quality products, must-know trends and fresh ideas for upcoming end-buyer campaigns.